Innovation in an Age of Fracture

Reflections from the World Government Summit

I’m just back from Dubai for the World Government Summit. The event, one of the largest apolitical gatherings in the world, offers a rare vantage point on the global innovation economy. It sits at the intersection of policymakers, sovereign investors, founders, and venture capitalists, groups that often talk past one another, but increasingly shape one another’s outcomes.

This year’s conversations were animated by a shared unease – geopolitical tensions and major technological innovations were certainly at the forefront of everyone’s minds.

I spoke on three panels.

Innovation and cross-border collaboration in Latin America, organized by Makhtar Diop and his team from IFC

Geopolitical tensions and its impact on startups, moderated by Bloomberg, fireside chat with me and serial entrepreneur Div Turakhia

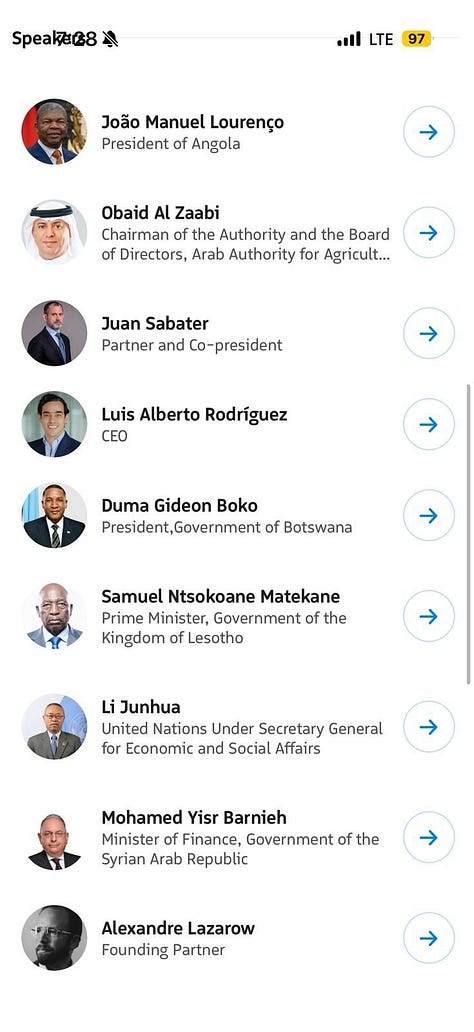

Emerging economies roundtable, with the Presidents, Prime Ministers and leaders of a few African countries, as well as private sector leaders (including me on behalf of Fluent Ventures)

Across many of the panels, the underlying question was not whether innovation would continue despite geopolitical headwinds. It clearly will. The harder question is where it will happen, who will lead it, and under what constraints or opportunities.

Several themes stood out from these conversations.

Geopolitics and Startup Risk: A Matter of Timing

One of the most persistent misunderstandings in discussions about geopolitics and startups is the assumption that geopolitical risk is evenly distributed across a company’s life cycle. It is not.

At the earliest stages, startups are not companies at all. As I deep dive in Out-Innovate, startups are projects in search of a business model. Their primary risks are intensely human and operational. Do the founders stay aligned? Do they find a product that customers actually want? Do they discover a viable distribution channel before capital or morale runs out?

For a pre-seed or seed-stage company, tariffs, sanctions, and trade policy are usually second-order concerns at best (for the average technology company). A founding team falling apart or failing to reach product–market fit will end the journey long before geopolitics has a chance to intervene. Startups that are succeeding can usually build workarounds on key barriers.

That changes as companies scale. At later stages, geopolitics becomes material. Supply chains harden. Regulatory exposure grows. Exit environments narrow or widen depending on cross-border capital flows, public market sentiment, and strategic acquirer behavior. IPO windows are political as much as financial. Margin of error en route to exits narrow. M&A increasingly reflects national priorities, not just corporate ones.

Tariffs and Trade Friction as Competitive Advantages

Trade tensions are typically framed as a tax on innovation. In practice, it is not black and white for all startups (as covered about our panel by Gulf News).

As global barriers rise, the advantage shifts toward local and regional startups. Regulatory complexity, tariffs, and industrial policy make it harder for global incumbents to operate everywhere with a single product and a single playbook. Local startups, by contrast, are born compliant. They understand domestic customers, pricing sensitivities, and institutional realities from day one.

This is a core thesis for Fluent Ventures, the VC fund I founded. We believe the best ideas are global, but the winners will be local. Tariffs, trade barriers and geopolitical fragmentation are part of this story. Rather than killing innovation, friction reshapes it.

Artificial intelligence accelerates this shift. AI dramatically lowers the cost of localization, from language and customer support to compliance workflows and product customization. What once required a global organization can now be achieved by a focused regional team with the right tools.

The result is not deglobalization, but regionalization. Instead of one winner taking all markets, proven models are replicated market by market. The future belongs less to companies that scale everywhere at once, and more to those that scale deeply somewhere first.

Global ideas remain porous. Execution becomes local.

Venture Capital and the Rise of the Camel

The venture capital model is evolving, but so are the companies it funds.

On the capital side, a barbell structure is becoming more pronounced. At one end sit mega-funds with scale, platforms, and the ability to underwrite geopolitical complexity. At the other end are smaller, specialist, and deeply local firms whose advantage comes from context rather than capital. The middle is thinning.

At the same time, founders are adapting to a more complicated geopolitical context, with higher interest rates, and constrained exits. They are reaching profitability earlier, managing burn more carefully, and building businesses that can survive without constant infusions of capital.

These are not unicorns optimized for a frictionless global market. They are camels built for uneven terrain.

Latin America Comes Into Focus

One of the more striking roundtable discussions focused on Latin America. The region is both a collection of isolated markets, but also home to some of the largest innovators around the world. In 2021, the largest IPO in the world was Nubank from Latam. A few years later, one of the largest M&As was also from Brazil (Pismo). I was joined in Dubai by Fluent portfolio CEO, Adal Flores, who leads Kueski, one of the largest BNPL providers in emerging markets.

Equally important is the rise of South–South collaboration. Conversations highlighted growing ties between Latin America and the Middle East, spanning capital, operating expertise, and market access. At the event, the President of Panama who joined our panel discussed the rising ties with Europe and Mercosur.

For founders, this opens opportunities to build with a broader emerging-market playbook. For investors, it creates a different kind of arbitrage: not just valuation gaps, but insight gaps.

Economic Development: Technology Is Not Enough

A recurring theme in economic development discussions was both optimistic and sobering.

Innovation and AI are seen as platforms for leapfrogging lagging infrastructure. South–south exchange offers real promise. Capital, knowledge, and talent moving between emerging regions can accelerate development in ways that traditional aid or extractive investment models cannot.

This is where geo-alpha is most durable.

But technology alone is insufficient. Digital tools cannot substitute for physical infrastructure, functional institutions, or credible regulatory frameworks. In the absence of these, technology risks amplifying inequality rather than reducing it.

The message from the private sector across panels was consistent that this groundwork was critical to scaling startups.

Playing the New Game

The global innovation system is not breaking. It is reorganizing.

The conversations at the World Government Summit pointed toward a clear conclusion. The future will not be won by those who assume a return to frictionless globalization. It will belong to those who can operate fluently across borders, stages, and systems, building companies that are grounded where they operate, but informed by the world beyond them.

In an age of fracture, local context is the new advantage.

![[99%Tech]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Vpj7!,w_40,h_40,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F288cd65c-980f-4acb-8182-1853ec1e444d_1280x1280.png)