The evolution of venture capital and the emerging manager opportunity

Guest Post: When Public Markets Experience Volatility, Experts Say To Invest In Emerging Managers

The S&P is down more than 20% so far this year. Technology stocks have fared far worse. The Nasdaq is down over 30%.

So where are pockets of opportunity in the space?

In this month’s guest post, Heather Hartnett, General Partner at Human Ventures, and fellow Kauffman Fellow argues that it belongs with emerging managers.

Read on.

This piece was originally published on Forbes by Heather Hartnett here.

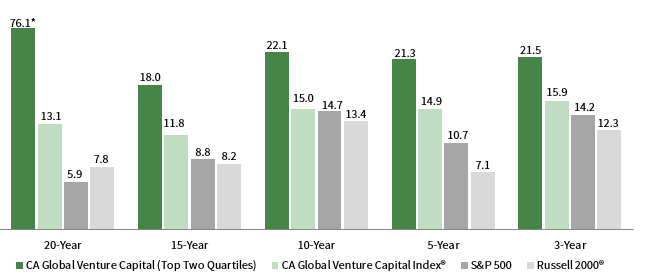

Brand-name growth funds may dominate the headlines, but an industry secret is that the best return profile in venture capital has historically been produced by the newcomers and at the early stages of investing. Data from Cambridge Associates shows that new and developing firms are consistently among the top 10 performers in the asset class, accounting for 72% of the top returning firms between 2004–2016

The early stage is where you’ll find the most emerging managers, by virtue of the fact that <$150m funds investing in pre-seed and seed companies are often earlier in their lifecycle. First funds are on the rise: the majority are <$25M and backed by individuals and families who are willing to take the risk on a manager with a shorter track record. It’s a smart bet, because the first three funds are when a manager has the most to prove and is working the hardest. They run a different calculus than later-stage funds: they’re optimizing for outsized returns to build their reputation, not for management fees.

They’re also likely starting their own fund because they see an opportunity they believe others are missing — which is what venture capital is all about.

Despite performing better than established funds, emerging funds are still underinvested in. Data from the NVCA and Pitchbook shows that less than 40% of venture allocations over the last fifteen years have gone to emerging managers. For endowments, emerging funds might not be able to meet their sizing requirements, but for family offices and newer fund of fund strategies, this opens up a big opportunity: better returns and easier access (through innovative manager selection, lower minimum commitments, and fundraises that stay open longer than the brand-name funds).

We’re starting to see more and more LP strategies emerge to capture this opportunity, which certainly substantiates the return potential. Even more established firms who have traditionally invested in “blue chip” funds have now raised dedicated vehicles for this vintage of seed managers.

Higher return profiles

For career venture managers who are strategic about portfolio construction, the path to outsized returns is, generally, to get meaningful ownership in future unicorns at the lowest possible entry point. The challenge is: how do you predict the winners?

For the LPs backing these managers, the question is how to get exposure to as many winners as possible. According to a recent report by Verdis Investment Management, the seed asset class is power law driven, which means there are a small number of outliers (1–2%) that drive almost all of the returns. Volume is a key part of their strategy: by getting exposure to 20% of the US Seed ecosystem, or 1200+ companies in strategic networks and geographies, they can increase the likelihood of capturing unicorns in their portfolio. Since it’s challenging to invest directly in enough startups for this strategy to work, that means investing in several seed-stage managers who each have a portfolio of 50+ companies.

Jamie Rhode of Verdis Investment Management explains, “We decided to do our own seed stage strategy in 2017, committing to 20 seed funds over four vintage years, and now have exposure to over 1,000 unique companies and 26 unique unicorns with an entry point at Series A and below in that portfolio. The results surpassed our expectations and we have now increased the cadence of funds we commit to.”

This strategy has added benefits when the public markets are experiencing volatility. While seed investing is risky (a seed-stage startup has an estimated 2.5% likelihood of becoming a unicorn), pre-seed and seed rounds are insulated from later-stage turbulence because valuation entry-points are generally still attractive.

Jamie shared data from a regression they ran that validates what we early stage investors recognize on a daily basis — there is little to no correlation between the current public market conditions and early stage venture returns since you are investing for an exit environment 8–10 years in the future.

While the power law dynamics of seed investing mean that volume can be a hedge, the “spray and pray” strategy of getting exposure to as many deals as possible is rightfully criticized. Finding the best managers who are going to be able to repeat success and consistently access the best deals is paramount.

Evaluating managers

As I’ve written previously, many emerging managers at one point grappled with whether to start their own firm or join an established one as a partner.

Once they’ve made the leap, emerging managers have the promise of high returns, but shorter track records. So how do you evaluate a great one?

Many of the best-performing funds in the VC asset class are the smallest, earliest stage funds, and many of those are run by emerging managers,” according to Alex Edelson, Founder and General Partner at Slipstream, a Limited Partner in early stage funds.

Alex says he looks for managers “whose investment strategy is tailored to their unique, durable competitive advantage, who have demonstrated that they add significant value to founders, and with whom founders and other investors love to work.” Understanding the right ownership targets for meaningful returns is important to him, too.

While there’s no one-size-fits-all background that spells success for an emerging manager, he finds former operators who can offer strong domain expertise to founders tend to have an edge.

Winter Mead, who runs Coolwater Capital, the studio and accelerator for launching and scaling emerging investment managers, agrees. He has seen VCs from a wide variety of backgrounds, “including those from finance, marketing, and PR that have each offered key skills and strategic advice that has helped founders and companies scale and get to the next level.”

Jamie takes the opposite position. She shared that “amongst the 38 seed funds we have invested in to date and that fit our general model, most are not ex-operators. This is typically because their portfolio construction does not align with the power law thesis we believe in a lot of shots on goal. A majority of ex-operator VCs believe in a concentrated portfolio and board seats where they can help create the next outlier.” She wants her GPs focused on picking outliers, not creating them — and definitely not trying to salvage the companies that are not viable.

“It doesn’t matter how much you own if you aren’t in a winner,” she says.

Non-consensus alpha

Getting access to startups early isn’t just about favorable entry-points, but being ahead of the market on larger trends, emerging sectors, and new profiles of entrepreneurs. Jamie notes that emerging managers “can provide differentiated and diversified access to a pool of startups that more established brand names may not have access to.”

Non-consensus alpha comes from spotting opportunities that are overlooked — often in underserved geographies and populations. Most of these opportunities are seeded by emerging managers, because even if established funds see these deals, they might not be comfortable taking the risk.

Coolwater sees inbound applications from over 1,000 aspiring managers each year, and works closely with a selection of these teams through its Build program. Winter shared, “In the last year we have worked closely with over 60 curated emerging managers. Sixty percent are from non-traditional VC cities (outside of SF, LA, NYC, and Boston) and over a third are international. Ambitious VCs are finding new opportunities to seek out founder talent and build innovation ecosystems in places that historically have been harder to reach.”

For LPs investing in seed, backing a group of similar managers that all have exposure to the same deals is not a strategy diverse enough to win. It’s far more advantageous to create an index of managers that are taking non-consensus bets with minimal overlap.

That being said, there are some trends that correlate to better returns: according to Jamie, geography (most winners come from California and New York) and networks (the value of the network a startup is in) can skew the likelihood of success.

During a downturn, be aligned with the builders

If the Great Financial Crisis of 2008 can be viewed as a proxy for our current downturn, we can expect funding to slow at the later stages, but new company formation and seed funding will continue unabated.

In fact, one of the most significant trends of the 2008 crisis was that new companies were built and funded at a growing rate — and revolutions in fintech and the sharing economy were born out of it.

A pullback like we’re experiencing now can actually have positive effects for seed investors: founders who want funding are forced to grow responsibly and focus on business fundamentals, like their path to profitability. Less hype will make it easier to separate the winners from the ones that won’t ultimately survive. It can be counter-intuitive, but the best times to build and invest are often when we’re most feeling the pinch.

![[99%Tech]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Vpj7!,w_40,h_40,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F288cd65c-980f-4acb-8182-1853ec1e444d_1280x1280.png)