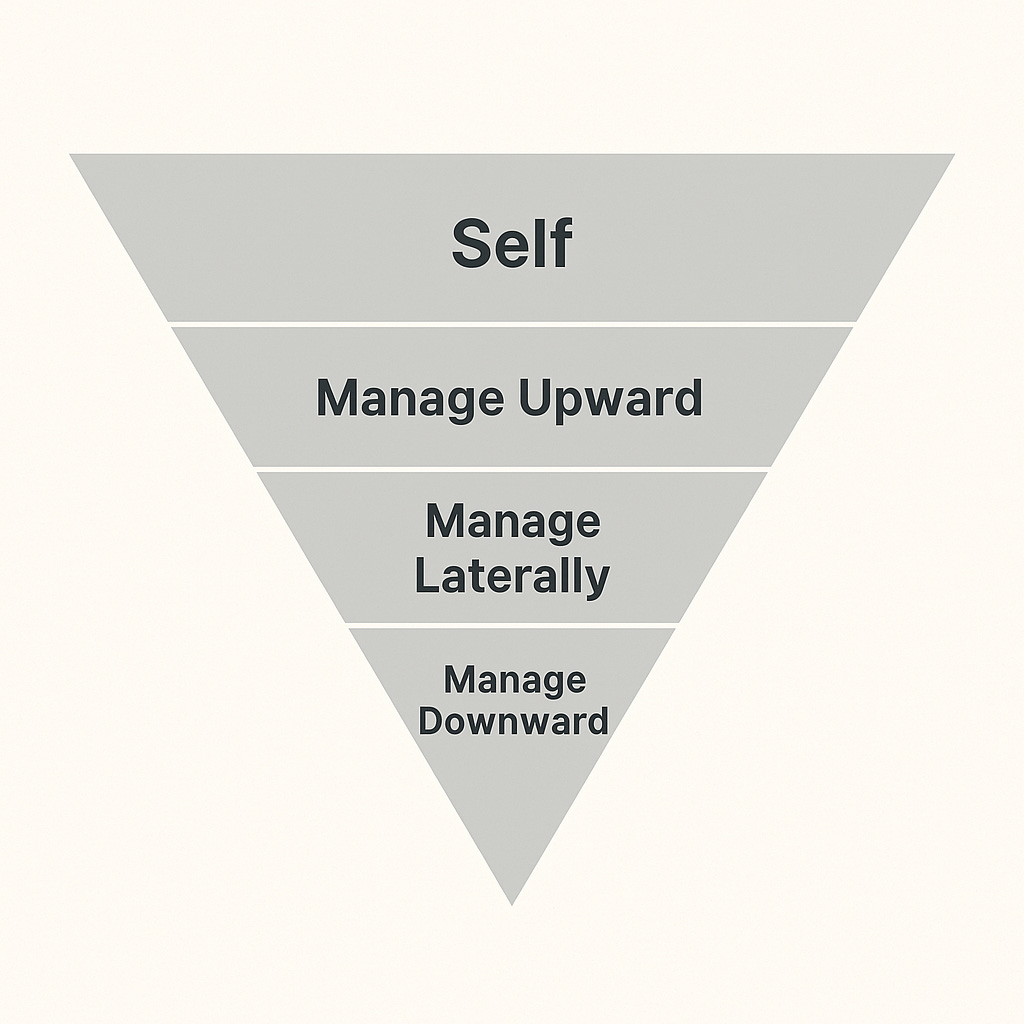

The Four Duties Of A Manager

The future of innovation is global. We discuss it here.

Before Visa was a trillion-dollar network, it was a scrappy community experiment led by Dee Hock.

I have had his book: Birth of the Chaordic Age on my bookshelf for years, and - taking advantage of the summer to catch-up on my backlog - have *finally* finished it (H/T Ben Goering for giving me the push).

One of the reflections I’ve loved the most so far was on the role of manager, reflecting on how Dee Hock’s observations can be applied to startups.

What do you think are the most important duties of a manager?

His answer is not what you think.

In this post I will share the framework. I wanted to share reflections specifically on what they would mean for founders as well.

1. First duty of a manager: Manage Yourself

“It is the management of self that should occupy 50% of a manager’s time and the best of one’s ability. And it’s the one thing that can never be delegated.” — Dee Hock

Before you lead a team, raise capital, or scale a product, you have to lead yourself. That means clarifying your values, mastering your emotions, staying grounded through volatility, and cultivating the discipline to focus on what truly matters.

In the volatility of startups, this is existential. Without self-awareness, founders overreact to setbacks, burn out, or make decisions rooted in ego. Without self-discipline, product strategy pinballs with every customer meeting or board request.

Self-management isn’t glamorous, but it’s foundational. Think of it as your internal operating system. Everything else runs on it.

2. Second duty of a manager: Manage Upward

In the startup world, managing upward means managing your customers, board, lead investors, and advisors. It’s not about appeasement or politics—it’s about active alignment and expectation-setting.

Founders often make the mistake of under-communicating or over-delegating this responsibility. But great founders treat their board not as a necessary evil, but as a force multiplier—when managed well.

That means:

Setting clear expectations

Pushing back with data and conviction when appropriate

Being honest and proactive, especially when things go wrong

Asking for help strategically

If you don’t manage your board, they’ll manage you. And not always in the way you want.

3. Third duty of a manager: Manage Laterally

Startups are forged in close quarters—often between a few co-founders and an early leadership team. Managing those relationships is as essential as it is delicate.

This involves:

Resolving tension before it festers

Disagreeing productively

Being clear about roles and boundaries

Balancing friendship with accountability

Peer management is tricky because it requires influence without authority. But it’s also where culture is set, especially in the early days. If trust doesn’t exist here, it won’t magically appear later.

4. Fourth and least important duty of a manager: Manage Downward

Ironically, the responsibility most associated with “leadership”—managing your team—is the easiest if you’ve done the others well. That’s why Dee Hock put it categorically last in importance.

Great founders don’t micromanage. They don’t try to have all the answers. Instead, they:

Hire people better than themselves

Create clarity of mission

Build systems of autonomy

Give feedback with humility and consistency

Crucially, they also allow their team to manage upward—creating the kind of recursive leadership loop Hock envisioned. If your reports are self-managing, and managing you upward, your job becomes less about control and more about enablement.

The Startup Paradox: The Most Visible Work Is Often the Least Important

Fundraising. Recruiting. Shipping product. These are the most visible founder tasks—and they matter. But they rest on a quieter foundation: how well you manage yourself and your key relationships. How you’ve built your culture, how much agency you’ve given your team and how you get the best of your people.

Hock’s framework flips the traditional org chart on its head. It reminds us that leadership is a function of self-mastery more than positional power. And that in startups—chaotic, fast-moving, and emotionally taxing—this hierarchy of responsibilities may be the difference between durable success and early implosion.

So next time you find yourself obsessing over how to manage your team, ask instead:

Am I managing myself? Am I managing my board? Am I managing my co-founder relationships?

Start with the hardest work. That’s where the leverage is.

![[99%Tech]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Vpj7!,w_40,h_40,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F288cd65c-980f-4acb-8182-1853ec1e444d_1280x1280.png)